Since spending a week on the Wind River High Route in 2022, Jim and I have been looking for another high-country objective. Andrew Skurka’s King’s Canyon High Basin Route initially looked appealing, but we eventually set our sights on the grandfather of high routes: Steve Roper’s Sierra High Route.

Due to family and work obligations, we did not have two weeks to hike 195 miles. Plus, we generally prefer shorter trips. Fortunately, the Sierra High Route has numerous off-ramps (especially to the East toward Bishop, CA). I marked Pine Creek, Rock Creek, and North Lake Campground as potential exits, calculating the added distance of each. I also set a series of ambitious projections on where we would need to camp to make it to Rock Creek, the farthest of these objectives.

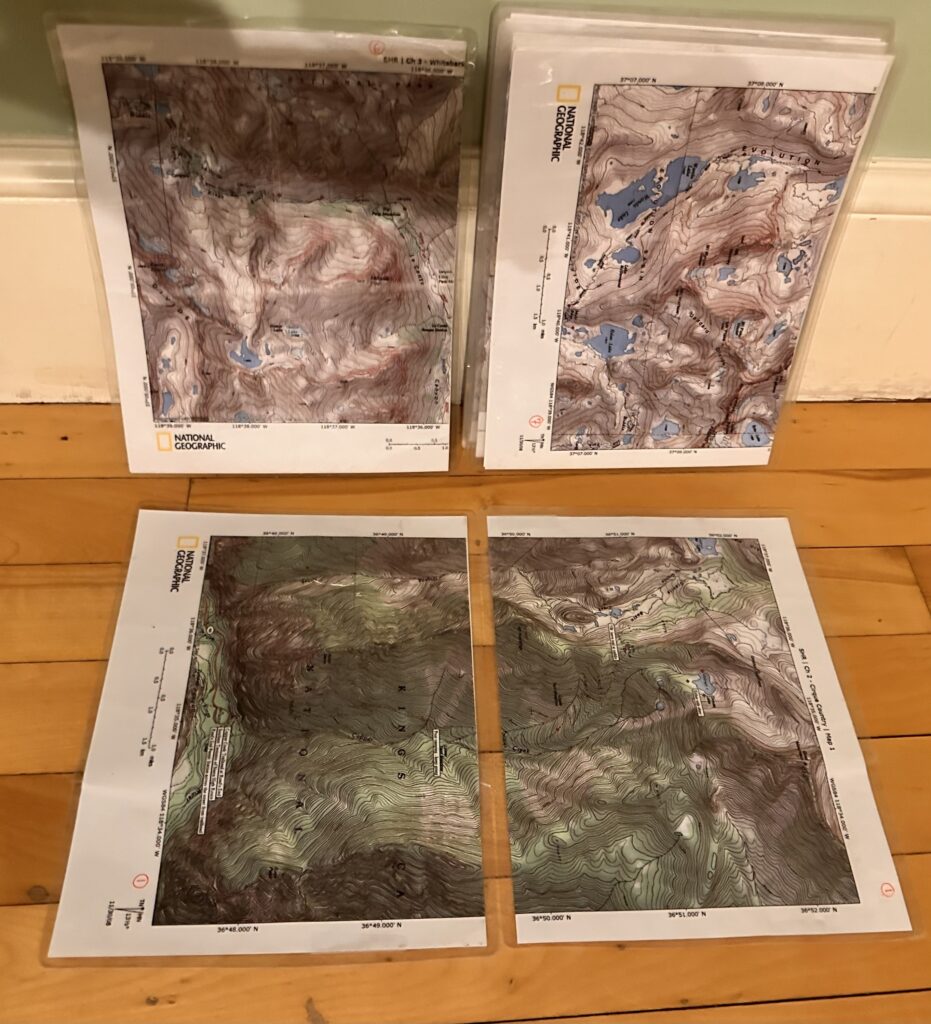

Additionally, I purchased Andrew Skurka’s map sets (available on his website). Many hikers on the route also used Roper’s guide. We sometimes regretted not buying his book, but Skurka’s rather sparse instructions provided all the needed information.

We ended up hiking from the start of the SHR at Road’s End in Kings Canyon to Humphrey’s Basin, where we exited after 6 (5.5) blissful days, following the Piute Pass Trail toward North Lake Campground. According to my GPS watch, we hiked nearly 80 miles averaging 3750 gross feet of gain each day. Our route was roughly 60% off the trail.

I highly recommend this section to those looking for a shorter Sierra High Route experience, mainly because of the proximity of North Lake Campground to the route, but also because this section covers some truly epic country. There is some consensus online that the first half of the high route (for northbound hikers) is the most scenic; I cannot say since I have not hiked it all (Piute pass is less than halfway to the end of the route going north).

From a JMT perspective, Evolution Basin, Mather Pass, and Muir Pass are well-known as especially scenic locations (that align with the SHR between its start at Road’s End and Humphrey’s). One added benefit of this exit is that it allows us to return later via the same trailhead and continue along the route with relative ease of travel. (Bishop has daily flights to and from SFO.)

Sierra High Route Day 1:

Kathryn dropped us off at Roads End in Kings Canyon on a hot, bluebird Friday morning. Having been in California for a week, we were all beginning to acclimate to the temperatures and elevation. Road’s End is in the middle of nowhere (over an hour’s drive from Grant Grove Village where we had spent the night).

It was already 11 in the morning! Jim and I were anxious to move, but we still had to do final gear organization and get our permits from the Ranger Station. It was going to be a late start.

Kathryn, Charlotte, and Margaret would make their driving through the canyon worthwhile by joining us for the first mile of our trip. On AllTrails, Kathryn had found a ledge that seemed an ideal turnaround for them.

The Copper Creek Trailhead was slightly removed from the Bubbs and Woods Creek Trailheads. It was also unique since it ascended the canyon wall with switchbacks rather than following the King’s River upward at the canyon’s end. From the first step, to where we left the trail, it ascended at an even grade of around 15 percent. Dry as the canyon is, we were weighed down with 4 liters of water. The elevation and heat also took some getting used to.

We found a rock ledge that may or may not have been their destination at the end of the switchback, so we stopped to say goodbye.

Our goal would be to stop every three miles for a quick break and drink consistently through our platypus water tubes. Glacier Lakes, our original goal for the day, would be impossible to reach before dark, but if we could cross Grouse Lake Pass, we would be in striking range of our goals.

We soon moved into a ravine indent in the canyon wall and contoured along the side. Plentiful trees provided some relieving shade, which we preferred to the scenic, but blisteringly hot ascent on the switchbacks of the initial canyon wall.

The trail became hard to follow in the grassy section of meadows and the sparse forest we crossed next. It was clear that it got less use than we had expected. We met a ranger packing out of the mountains with a huge trash bag. We stopped to talk briefly, and he asked about our permits. Thank god for rangers!

At Upper Tent Meadow, we again enjoyed the impressive scenery the beginning of the Copper Creek Trail had offered. Trees speckled a grassy slope that’s descended to the Canyon edge. Beyond the canyon, we saw the high peaks of the Southern Sierra, most bare of trees and snow.

From the meadows, it was clear that there would be a great deal more climbing; our maps clarified that we still had 2000 feet to gain before reaching Grouse Lake. Nearing the end of a steep section with numerous switchbacks, we met a European couple descending. They were enthusiastic about Granite Lake, nearby and assessed by trail, but had no idea about Grouse Lake, or the junction we were anticipating just above where the wall’s crest met blue skies.

We soon clarified the confusion about the junction (or lack thereof) when we realized we’d passed it. It soon became clear that the Grouse Lake Trail was little more than a goat path. After a painful half mile trying to follow the trail, we gave up and set a line toward the lake’s drainage. This was effective, and we soon crossed the boggy meadows and slabs of rock directly beneath the lakes. At the outlet, we stopped for a second meal to energize before climbing Grouse Lake Pass.

Contouring around the lake was incredibly rewarding. We took a slight route-finding risk by following a shelf to the left and quickly found ourselves on the other side.

We decided to camp in the upper reaches of Granite Basin, beyond the pass. We may have been able to contour along the upper wall to Goat Crest, but we had to drop to the basin floor to camp. Besides, the line along the top looked as though it risked being gnarly and tiresome. Having refilled at Grouse Lake, we did not top off our water supply at the streams in the basin. Carrying four liters was certainly excessive. We were weighing ourselves down! We had anticipated a drier Sierra, but later learned it had been a great snow year, hence why we had seen plentiful water everywhere! Thanks to shlepping 13 pounds of water over the pass, we did not have to filter in camp. The sun set before we were finished our dinner.

Sierra High Route Day 2:

We set out toward Goat Crest with less than a liter of water (left over from the day before) since the water near our campsite was brackish. There would be water over the pass at Glacier Lakes. The ascent to Goat Crest was not what we had expected: much of the climb followed a grassy slope and there was always some flora for our boots to grip on the steepest sections. We would be in for a treat if all SHR passes were similar to this one. Our packs were quite light without water!

We expected to have to push to Glacier Lakes to fill up, but there was a tarn just over the crest. We stopped to fill 3 liters each. In retrospect we would have only carried one at a time, drinking when we found water, especially in a region with so many alpine lakes.

The descent from Goat Crest was short and steep. Upper Glacier Lake was situated in a wide basin, so we had no difficulty crossing the grassy bank on the left side of the lake. A carpet of flowers stretched downhill between the lakes, making this one of the most picturesque locations we passed on our trip.

At the lower Glacier Lake, we stayed right, contouring through sparse trees and boulders until we reached the steep headwall of the drainage (which we descended from the left). Below there were two marshy meadows and an expanse of forest. We knew that beyond the second meadow, we would join the State Lakes Loop Trail which would take us out of this basin.

For some reason, despite the relative beauty of our woodsy surroundings, I was super anxious to get out of this basin. It must have been the time of day. Still, I enjoy hiking more when not focused on reaching the next waypoint.

The trail was not especially well-defined but not hard to track either. There was some climbing, but we were completely below the treeline, which is very high in the Sierra. The junction for the Horseshoe Lakes Trail was where our luck ran out; the trail was almost impossible to follow. It took some time for us to give up on that end and to take a bearing toward the Lakes.

After stopping for lunch between two idyllic lakes, we were slated to ascend Windy Ridge. Initially, we balked at the steep headwall visible from the lake, but it turned out that Skurka had us contour around the steep wall and the ridge, following a shelf to the north. Thanks to Roper’s ingenious route planning and Skurka’s maps, we gained the ridge via a climb carpeted in pine needles, not talus or scree.

I hoped Windy Ridge would live up to its name, but it did not. A bit of wind would have provided relief from the oppressive heat. We concluded (logically) that it would be best to follow the flat bench and drop to Grey Pass once we reached it. That worked brilliantly! A chute took us down 200 ft to the pass.

Grey Pass offered a great view that straddled two basins. I guess the rock nearby was grey (hence the name). We descended steeply into the basin below, dreading the 1500-foot ascent to White Pass, visible above. Water was again plentiful, and we had to hop some rushing streams to reach our next ascent. Though much longer, our contouring route was gradual compared to climbing straight up the pass as Skurka’s maps appeared to suggest we do.

White Pass presumably gets its name from snow, though there was none this late in the season. It was a midevil climb to the final 11,700 ft elevation. “One foot in front of the other” was our maxim to the top.

The topographic lines on our map failed to account for the true separation between White Pass and Red Pass. They are distinct! Fortunately, we lost little elevation contouring around a ridge to reach the second pass. It was only a half-mile crossing.

I felt spent once we crested into the shaded basin beyond the pass. It had been a monumental day with four major ascents/descents. On the way down, I fell and damaged some equipment. Fortunately, there was camping just below and the views were gorgeous. Vacillating between awe and exhaustion took me the final mile to a knoll overlooking Marion Lake.

We were thrilled to be within striking distance of whichever goal we set for later in the trip. Our campsite was one of the most scenic I’ve ever spent the night in.

Sierra High Route Day 3:

Jim and I decided to try an idea he thought might increase our productivity: making breakfast an hour into our hike. This plan would allow us to pack out of camp before seven comfortably. The descent to Marion Lake was steep! The leftmost approach closer to the middle of the lake was the only passable option, and it was a steep talus slide!

Marion Lake was the darkest blue I have ever seen. An unbelievable hue!

Having hugged the left side of the lake to cross toward the Lakes Basin, we began our first ascent of the day. We were sure we would soon reach an ideal lake for breakfast. Unfortunately, the only mosquitos we encountered on the trip frequented these lakes. Neither of us wanted to be breakfast for them, so we continued climbing headwall after headwall, each separated by a new lake and drainage until we were out of the bugs’ range.

By the time we had finished our hot breakfast, we had nearly run ourselves out of water, but there was none immediately nearby, so we had to continue hiking. Finally, we ascended into the last canyon before Frozen Lake Pass and found sweet H2O. With all this stopping and starting, we had allowed the sun to rise higher and higher and barely had moved.

To make matters worse, my nose suddenly began gushing blood. I had to climb the steep pass with a tissue in my nostril!

The descent from Frozen Lake Pass was not bad by Wind River High Route standards, but for the SHR, it sucked. With cascading scree, we slid to a brief respite on the glacier, before crossing some gnarly ankle-grabbing talus by the lake.

The snow sitting in the lake made a quick swim look extra refreshing, but it had to be pretty cold. Still, my interest in photographing the sub-surface glacier almost propelled me toward an involuntary dip.

Endless talus separated Frozen Lake from the floor of the basin. We painstakingly crossed this, looking for an inch of lunchtime shade. After contouring around a bluff, thinking we’d finished our tiresome descent, we realized the basin floor was another steep talus field below us. That did it! We found a boulder that provided just enough shade to eat our bagel sandwiches in peace before braving any more talus.

Once we’d reached the basin floor, the going was quite easy. We gained a ridge and found the JMT! It did not disappoint. Suddenly, we were meeting hiker after hiker. Having not seen anyone since the Copper Creek Trail, this change was somewhat exciting. We were speeding through this section, and it felt great! It took us 40 minutes to cover the 2 miles between where we joined the trail and the top of Mather Pass. Mather Pass was over 12,000 feet (like Ice Lake Pass), but the elevation was not a problem this far into the trip.

After Mather, we met another SHR hiker! He stopped to ask what we were doing, recognizing our gators and trekking poles. He was southbound and gave us some insight into the terrain ahead. We realized what we were missing with Roper’s guide, as he explained the best approaches to various passes.

The Palisade Lakes filled the basin below us, but the JMT switchbacked and switchbacked, aggravatingly forcing us to put in more miles than we would off trail. We were unsure where to camp; we had time to continue toward (or over) Cirque Pass, but we did not want to turn our vacation into a slog-fest.

It was good to have an extra hour in camp to consider routing options and read the book I’d shlepped into the wilderness: Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night.

Sierra High Route Day 4:

The only downside to our campsite was the water situation. We had heard water trickling nearby when we’d pitched our tent but later realized scrub surrounded the stream. I had to climb above our campsite a bit to filter, but it all worked out.

In the past days, the sky had been an uninterrupted blue, so we were grateful for the clouds that had appeared in the sky overnight. We slathered sunscreen on our sunburnt arms and legs just after leaving camp.

The trail through Palisade Basin sloped downhill. We hoped to make good time up to Cirque Pass since we had spent so much time climbing Ice Lake Pass the day before. Palisade Basin was gorgeous! We passed many hikers; everyone was thrilled to be there. It was sad leaving the JMT at the lower lake’s outlet. Some nearby campers looked confused, as we veered upwards, off the trail.

Initially, we had to climb rock slabs to ascend toward Cirque Pass. Jim and I picked different routes to see which was faster; that entertained us for a while. We met a duo, on a backpacking trip, who were day hiking up Mt. Sill from the JMT. They were the only people we saw on any off-trail SHR segments. We passed a beautiful tarn, whose surface was the only flat ground in the area. The slabs kept getting steeper as we progressed until we were hand-over-hand climbing, but the going was easier than talus.

Soon enough, we reached another tarn and our slabs disappeared under a thick cascade of talus. Oh, well!

We followed the right edge of the talus field to the pass. Upon reaching the crest, we realized we had climbed extra. The pass was below us (to the left). Jim bit the bullet and descended a bit, but I tried contouring.

(I beat him to the “real” pass.)

The peak far to the right is 14,160 ft Mt. Sill (where the climbers we met were headed). Mt. Sill seems like an epic climb. We would have considered adding a day to bag it from the Sierra High Route. It is known to be technical, so I’m not sure how accessible the summit would have been for us.

Potluck Pass is on the Sierra High Route. North Palisade and Mt. Sill are popular climbs that are generally remote, but easily accessed from the SHR.

The descent between the lake and the pass was one massive slab. Jim and I decided we would go straight down. That was a thrill! We stopped for a snack by the lake.

After the lake, we almost immediately began ascending to the opposing side of the cirque. Little did we know we would have to drop down again before reaching Potluck Pass. We crested what we thought was the pass, only to find a second lake. This section was particularly scenic.

Potluck Pass consisted of grassy patches and slabs instead of talus. There was an ideal route evident from the base of the pass.

Barrett Lakes and the Palisade Basin were the next stops on our itinerary. Dramatic Polemonium, Starlight, and Thunderbolt peaks towered to our right as we contoured from the pass toward Barrett Lakes. Our maps told us to stay high, so we followed the route of least resistance closest in elevation to the pass. Then, we followed a drainage toward the lakes. We filtered and ate at Barrett Lakes but regretted descending to the lake’s edge. We had to climb back above the left side of the lake to move toward Knapsack Pass.

At the outlet of Barrett Lakes, we gave up on the path of least resistance and set a course straight toward Knapsack Pass. The terrain was so gnarly, that there was little reason to try to beat it.

Knapsack Pass was not far above the drainage we followed to its base. It was likely the easiest of all the off-trail passes we crossed (at least in terms of the ascent).

The Dusy Basin crossing was less inspiring than its scenery. We had to contour along a ledge to reach the Bishop Pass Trail. There was no flat ground. The clouds provided occasional relief from the sun. Finally, we found a marshy drainage that allowed us to cross toward the trail more effectively.

Once on the trail, we rapidly covered ground. We passed a group of rangers, packing out of Dusy or doing trail work. We could not guess which; the trails seemed to be in near-perfect condition.

We were unsure if we’d find secluded camping, as we plunged deeper into the valley, knowing the JMT would be lined with tents. The evening light in Dusy was gorgeous, and we hoped to find flat ground before reaching Le Conte Ranger Station in the canyon below. Just as we gave up hope, having descended below the tree line, we found a heavily trafficked campsite overlooking a ledge. The view was astounding!

We did not expect to enjoy a campfire on our trip, due to regulations that only allow them in existing firepits below 10,000 ft. The stars aligned for us to have one, though, since our 9,500 ft campsite had three existing fire pits and a homemade bench! We took advantage of the plentiful dry kindling on the ground. Unfortunately, there was evidence that someone split wood here in the past. Still, despite the apparent human activity, the view was unbelievably picturesque.

Sierra High Route Day 5:

We started packing camp at 5 AM, knowing it would be a lengthy day. We had decided to leave the Sierra High Route at Humphrey’s Basin, since we did not want to follow just slightly more of the high route to the intersection with the French Canyon Trail or Lake Italy, only to slog 11 miles out to Pine Creek. With a big mileage push on day five, we could easily make the North Lake Trailhead within the next 1.5 days. Besides, we knew we would be satisfied with six days.

Interestingly, we passed a sign by a fenceline through the trees that referred to livestock. We did see evidence of horses on the trail, as well. Maybe they are used for trail work near LeConte! However, we were in a wilderness area.

We soon came to the junction with the JMT. We had lost a whopping 3,500 ft from Knapsack Pass. As soon as we turned right and onto the JMT, we began the gradual ascent that (over eight miles) would take us to Muir Pass.

We power-hiked in silence, passing many tents along the Middle Fork of the King’s River (which the JMT follows upward). Some hikers waved, as they filtered water in camp. We leapfrogged them later after we stopped for a snack. I found it intriguing from a geographical perspective to be near the Middle fork of the King’s River since we had started in King’s Canyon, formed by the South Fork.

The trail steadily climbed out of the trees into a barren, craggy canyon. We soon passed more alpine lakes and reached the base of Muir Pass. We were hoping to make it to the top by 10:30 AM and were ahead of schedule.

The JMT had become a highway by early morning, and we met hikers every few minutes. One group was desperate for oral antibiotics, but unfortunately, we had nothing to give them. We hoped someone had brought an old prescription in their first aid kit for their sake.

Enormous Lake Helen was in stark contrast to its dry surroundings by Muir Pass. The JMT was taking its sweet time getting us to the top of the pass by switchbacking, and 10:30 was fast approaching. We made it up just before the deadline!

Muir Hut was a super cool storm shelter at the pass. What an awesome way to memorialize John Muir!

The terrain stayed dry after the pass, and the sun was beating down hot. We were grateful for our early start. The JMT was relatively direct between Wanda Lake and the pass. We hoped to find some shade for lunch (to no avail).

We stopped by Wanda Lake to filter and rest in a blooming field. We even found a boulder to rest our backs against. After dropping below the lake, we entered the beautiful Evolution Basin. The JMT sloped gracefully down toward Sapphire Lake. The basin was paradise; there were streams to cool off in and rocks to climb on. (We did not swim, but I did splash some water around.)

Interestingly, we weren’t seeing many backpackers on this side of the pass, but we were looking forward to getting off the trail. When we were off trail, we couldn’t wait to get back on; when on trail, we eventually started anticipating the deep backcountry.

Soon enough, we rounded Evolution Lake, where a large group had set up tents. It was vibrant between the landscape (which looked straight out of Jurassic Park) and the people swimming in the lake. Finding a better spot than Evolution Lake to chill in the mountains would be an epic feat.

I was glad to have brought a pullover because we were both getting increasingly burnt despite all the sunscreen. I put it on for some UV protection. In the future, we will wear these instead of carrying heavy sunscreen.

Soon after stopping in Evolution Basin, we reached the switchback where we were meant to leave the trail. The Lamarck Col Trail also began there, but we only followed it 100 ft before contouring West. Some SHR hikers continue up the trail toward Alpine Col, shaving off the cumbersome slog, through brush and between cliffs, to Lake 11106. That route also avoids the hairy Snow Tongue Pass. However, given our more relaxed itinerary (and Skurka’s maps), we continued onto the shelf.

Crossing the shelf was brutal. We continuously lost and gained elevation, dodging obstacle after obstacle. It felt like we were making no progress, despite our efforts. It had been just 3 PM when we reached Evolution Lake, but now we were only moving at 3/4 of a mile per hour. Again, we remarked that we were grateful for our early start.

After a quick break, we realized that despite being little more than halfway along the shelf, we would soon enter slightly more gentle terrain. We also counted two stream crossings before a particular drainage (which we would follow up to camping in the basin above). It was fun to move a bit faster, and have the streams as waypoint motivators.

Once we reached the drainage, we climbed quickly toward Skurka’s marked camping, a pancake flat clearing by a stream. We stopped to rest before setting up camp.

Sierra High Route Day 6:

The morning of day six was frigid. It did not help that we had not set up the rainfly over our tent. We woke to find our sleeping bags, packs, tent, and seemingly everything else in camp coated in frost. I found it difficult to mobilize in the freezing air, but a warm breakfast and many layers helped ease the process. The sole advantage of our rainfly mistake was seeing the night sky, which is brilliant in the Sierra.

It took a decent amount of hiking to warm up since the ridgeline ahead of us blocked direct sunlight. The remoteness of our location was striking. To access this basin, hikers would have to take the gnarly approach we had to take, climb a steep route from the canyon below, or cross the other side of the pass.

Leaving the grass behind, we crossed talus fields, following a lake-filed drainage toward Snow Tongue Pass. The grass was almost slick with all the frost.

The Snow Tongue Pass ascent was relatively brief. Jim decided to contour far to the left of the pass, though he ended up having to cut right back over. I went straight up and had no trouble with the slabs and boulders. Snow Tongue Pass is on the Glacier Divide, and the peaks nearby are dramatic.

Since it was still early morning, we climbed to one of the nearby peaks. Wahoo Peak stands at 12,487 feet but is pretty well removed from the pass. We climbed one of its false summits to see Humphrey’s Basin and Mt. Goethe from a higher vantage point. The climbing (on slabs) was easy and non-technical, but we found a dramatic perch at the destination.

Once back at the pass, we thought we’d have a relatively straightforward, but demanding decent. We saw a “trail” that turned out to be a mess of scree and loose dirt. I descended first, soon realizing that there was nothing for this route. If we wanted to descend safely, we would have to hug the cliffs to the left of the pass. We remembered then, somewhat ironically, that the SHR hiker we’d met on day three had told us to hug the left cliff. Oh, well! Once we were on the right track, the going was no harder than your average pass on the Wind River High Route

There was even a glacier to cross in between sections of talus.

The talus fields between the pass and Humphrey’s Basin were rough. The going was so tedious— and it never ended. The ankle-grabber talus felt more dangerous than descending the wrong side of the pass.

We reached Humphrey’s Basin by Golden Trout Lake, named for the endangered species inhabiting it (camping is prohibited in this area). We even saw a trout, though we could not say whether it was of the golden variety. One of the trip highlights was a bold leap between boulders that allowed us to cross between two lakes, rather than contouring around.

We gained a ridge, fearing that we might end up descending again. Fortunately, we had made the right call by climbing. We could follow the crest toward Piute Pass.

While filtering water near the Muriel Lake inlet, another hiker crossed the stream in the distance. Initially, we thought he was also off-trail, but we met a second hiker by the lake, who explained we had just intersected the Golden Trout Lake Trail. He had no idea what the Sierra High Route was. We continued in opposite directions, as he climbed into the Goethe Cirque.

The Golden Trout Lake Trail was a perfect surprise. It took us directly up to Piute Pass.

There was a popular day hiking route to the top of Piute Pass, and we began meeting hikers as soon as we joined the Piute Pass Trail toward North Lake Campground. We were ready to get to the trailhead and secure a ride back into town.

A nice lady reassured us that if we had not found a ride by the time she got to the trailhead, she would give us one. That saved us from worrying about how busy the trailhead might be. We also met a hiker who had been a teacher in Long Beach. He had led a hiking group at his school. Hiking always attracts great people, but I’ve noticed that Californians are exceptionally friendly.

We arrived at the trailhead, which had limited parking. There was a campground, but we could not find where all those hikers we had seen on the trail parked their cars. We knew we would need to find the parking area to get a ride, but after walking down the road, we decided to stay at the trailhead. One couple offered us a ride to Aspendell, a nearby town outside of Bishop, but we stayed at the trailhead, betting we could find a ride straight into town.

Then, the person who had offered us a ride earlier reached the trailhead. She was incredible! She had started hiking later in life and had gotten into ultralight backpacking, now carrying a 22 lb pack! Our heads exploded at that pack weight. She even planned to hike the JMT at age 75!

She explained that the hiker’s parking lot was farther down the road, setting a brisk pace towards it. We were so grateful to her for her kindness and for getting us to Bishop!

Notes:

The Sierra High Route is some paradise! In contrast to other reports online, it never rained once; we only encountered serious bugs once. Six days felt like the perfect duration to get into the hiking, but not overdo it. As stated above, I recommend this plan for anyone looking for a week on the Sierra High Route. I am so grateful for this experience and everyone who made it possible.

Stats:

D1: 6000 ft of gain; 10.5 miles

D2: 4000 ft of gain; 14.5 miles

D3: 3300 ft of gain; 11 miles

D4: 3040 ft of gain; 11.75 miles

D5: 4300 ft of gain 19.2 miles

D6: 1750 ft of gain; 9 miles

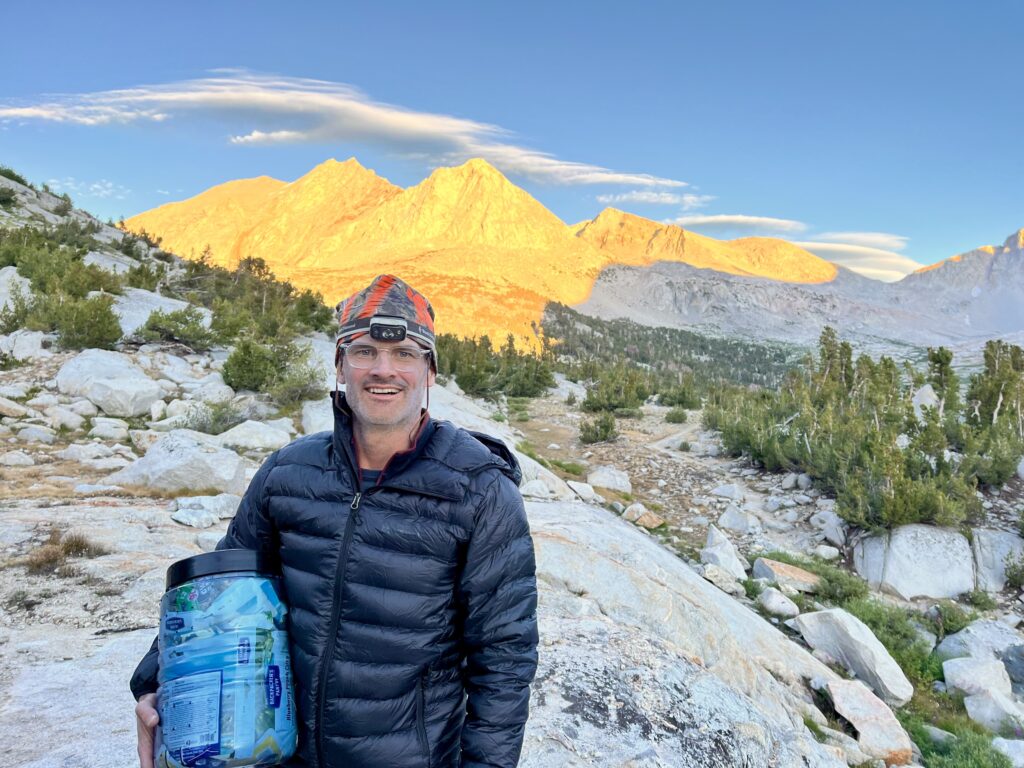

Ben, these are absolutely stunning photos. I have to go back through and read everything again. You have a definite talent of capturing the Sierra and viewing it through your eyes was a pleasure. You are one gifted young man and it’s a pleasure to follow your adventures. Definitely Magazine Quality Photography. You should market these. Backpack on…Sir Ben!

Thank you so much!! That means a lot, and I am so grateful to have been able to capture it. That is too kind!

Remarkable trip, and quite a detailed post! If you have a moment can you add images of the topo maps you used and the route laid out on them?

Mapping details are a fine line to walk with high routes for sure! Roper requested that people not distribute their tracks when he released his book on the SHR, since the route finding is a big part of the SHR experience. However, I made a more general line using Gaia GPS for orienting the route on the map (hopefully without offending anyone). We used Gaia in tandem with Skurka’s commercial waypoints. I inserted the map at the end of the post!

Thank you for your great story telling! I’ve vicariously hiked through you!

Hey – this was exactly what I was looking for, thank you! What was your process of getting to/from the trailheads at the end? I’d live to do a point to point hike like this but don’t know how the logistics work.